|

|||||||||

|

|

<< Previous | Contents | Next >> CHAPTER XIV THE TURN OF THE TIDEThe German presentiment of disaster was justified by events in the spring of 1917, and the new British Government seemed to have come in on a flowing tide. In spite of the gloomy picture of the situation which Mr. Lloyd George had drawn for his chief in December, confidence in a speedy victory animated the appeal of his ministry for further financial support; and in most of the spheres of war the first quarter of 1917 saw the reaping of harvests sown by other hands. The deferred dividends on the Somme campaign were paid, and the Germans fell back from hundreds of square miles of French territory. Mesopotamia was conquered as the result of the patient labours of Sir Charles Monro and the brilliant strategy of Sir Stanley Maude, who had been appointed in August 1916. The meagre German holding in East Africa was further reduced; and even distressful Rumania put a stop to the German advance.

Security for the Rumanian forces could not, however, be found short of the Sereth, which would give them a straight line with the Russian frontier protected by the impassable delta of the Danube on their left, and a flank in the Carpathians on their right; and from the fall of Bukarest to the end of December Averescu the Rumanian commander, and Presan his chief of staff, retreated to this line fighting rearguard battles on the way. The most stubborn of these was a four days' conflict at Rimnic Sarat in the centre on 22-26 December, after which Mackensen entered the town on the 27th. Sakharov conformed to this retreat in the Dobrudja; on 4 January Macin, the last place east and south of the Danube, was evacuated, and on the 5th Braila on the opposite bank south of the Sereth and Danube confluence. On the 23rd the Bulgarians, taking advantage of the unprecedented frost, crossed the marshes at Tulcea, but were annihilated by the Rumanians on the northern bank, and remained content for the rest with the defensive. The same wintry conditions put an end to fighting at the other extremity of the line in the Carpathian passes, but in the centre Mackensen seized Focsani on the 8th and occupied the bank of the Sereth. That line had originally been fortified against the Russians, and it faced in the wrong direction; but the position was strong, and when on the 19th Mackensen sought to force it he was repulsed in a costly encounter. Russian reinforcements which might have saved Wallachia came in time to protect Moldavia; and the war-worn Rumanian army was retired to refit, the defence of the Sereth being left to the Russians. The Germans made the most of their booty in Wallachia, which suffered the fate of Belgium and of Serbia; though the stores of grain had been burnt and the Rumanian oil-wells put out of action for many months. In one respect Rumania was less fortunate than the other little nations: in his fanatical hatred of Russia, Carp rejoiced in her ally's defeat--albeit that country was his own--and Marghiloman remained in Bukarest to curry favour with its conquerors, and ultimately to become for a brief and discreditable period the Premier whom the Germans imposed on Rumania after the Treaty of Bukarest. Meanwhile the patriotic parties rallied round the ministry at Jassy and formed a Coalition Government. The defence of Rumania now seemed to occupy all the energy Russia could spare from her domestic preoccupations. In January there was a sound strategical effort to divert German attention from the south by a counter-offensive from Riga, and an advance of some four miles was made to Kalnzem. But the Germans soon recovered most of the ground; and elsewhere the front was quiescent. There was no repetition of the great blow at Erzerum of January 1916, and in Persia Baratov's small but adventurous force was driven back by the Turks from Khanikin to Hamadan, and the resistance to Turco-Teutonic invasion and intrigue was left more and more to British effort. Co-operation seemed impossible to synchronize in the East; one partner retreated whenever the other advanced. While therefore the Russians halted in Asia Minor and withdrew in Persia, Sir Stanley Maude was gathering his forces for a spring on Baghdad. Gorringe had already in May 1916 advanced some way up the right bank of the Tigris towards Kut; but summer forbade active operations, and Maude had been duly impressed by the force which previous experiences in Mesopotamia had given to the adage about more haste and less speed. The autumn was spent in careful study and preparation, which would preclude a repetition of the retreat from Ctesiphon and the fall of Kut (see Map, p. 177).

By 12 December he was ready to attack. The Turks still held the Sanna-i-Yat positions on the left bank of the Tigris, but on the right they had been pushed back to a line running across the angle from the Tigris at Magasis towards its southern tributary the Shatt-el-Hai. The Turks under their German taskmasters had not been idle, and this angle, as well as the extension of the Turkish line along the Shatt-el-Hai and their secondary defences on the right bank of the Tigris above Kut, had been well protected by trenches and wire entanglements. The breaking down of these obstacles required stubborn fighting as well as skilful tactics, but the only alternative was to penetrate the Sanna-i-Yat positions and they had proved impregnable in the spring. A serious attempt had, however, to be made at Sanna-i-Yat in order to detain there a serious Turkish force; and while Marshall pushed his way through on the right bank, Cobbe was kept hammering on the left. On the 13th crossings of the Shatt-el-Hai were effected at Atab and Basrugiyeh some eight miles from Kut, and Marshall advanced on both banks to Kalah-Hadji-Fahan. On the 18th he reached a point on the Tigris just below Kut in the Khadairi bend. Rain and floods then impeded our advance for a month, but the Khadairi bend was gradually cleared of the Turks, and most of their positions in the angle of the Tigris and Shatt-el-Hai were taken. On 10 February Marshall pushed on beyond the Shatt-el-Hai, reached the right bank of the Tigris above the Shumran bend, and by the 16th forced the Turks in the Dahra bend across the river. The Turks had now been driven off the right bank below, in front of, and far above Kut, but they held the left bank as far down as Sanna-i-Yat, and Maude's task was to find a way across. He chose the Shumran bend, but diverted the attention of the Turks by thrusting at Sanna-i-Yat from 17 to 22 February. On the 22nd he also made feints to cross at Magasis and Kut, but on the 23rd the real attack was made at Shumran. Troops were ferried across and a bridge built before evening, and on the 24th the Turks were driven back on to their lines of communication between Baghdad and Kut. Meanwhile Cobbe had forced six enemy lines at Sanna-i-Yat and then found the remainder deserted. The Turks were in full retreat towards Baghdad, and Cobbe entered Kut unopposed. The pursuit was taken up by Marshall, who reached Azizieh in four days. There he halted till 5 March to prepare for his final advance. On the 6th he passed deserted trenches at Ctesiphon, and on the 7th reached the Diala. For two days the Turks disputed the passage, but a force, transported to the right bank of the Tigris, enfiladed their position on the Diala and captured their trenches at Shawa Khan on the 9th. Our forces on both sides of the river entered Baghdad on the 11th, thus concluding a model campaign which reflected glory alike on the British and Indian troops engaged and on their commanders, and raised British prestige in the East higher than it had been before the fall of Kut. The work of our armies in Egypt was less sensational, but it was making solid progress and laying firm foundations during the autumn of 1916. The Grand Sherif of Mecca was proclaimed king of the Hedjaz, and he was a thorn in the side of the Turks. Their defeat at Romani had been followed by the steady construction of a railway eastward across the desert from Kantara, and on 20 December El Arish was captured, while on the 23rd the Turks who had fled south-east to Magdhaba were there surrounded and forced to surrender. The success was repeated at Rafa on the Palestine frontier a fortnight later, and presently the whole Sinai peninsula was cleared of the enemy forces (see Map, p. 352). Early in February a final blow was struck on the western frontiers of Egypt at the Senussi, and Egypt was converted from an enemy objective into a fruitful basis of operations against the Turkish Empire. Whatever might be said for frontal attacks in the west of Europe, ways round were proved to be the shortest in the East, and the failure of the direct blow at Turkey's heart in the Dardanelles was redeemed by success along the circuitous routes through Egypt and Mesopotamia. Among the other forgotten achievements of the first two and a half years of the war was the completion, chiefly by British arms, of the establishment in the African continent of Entente and mainly British supremacy. For even before the Turks had been driven from the frontiers of Egypt the Germans had been expelled from all the important parts of East Africa. The progress had been slow and not very creditable to our earlier efforts, which failed through an underestimate of the German strength, and particularly of the skill and resource of the German commander Von Lettow-Vorbeck. But it was sound as well as inevitable strategy to make sure of what we had by suppressing rebellion in the South African Union and then securing its frontiers by the conquest of its German neighbour before proceeding to concentrate forces for an offensive against an isolated German stronghold which could not threaten any essential interest nor affect the main struggle for victory in the war. The case against divergent operations was strongest of all against the East African campaign; and it would have been criminal folly for the sake of amour propre or imperial expansion to diminish our safeguards against a German victory in the West, or weaken the defence of our threatened communications with Egypt and India. Von Lettow-Vorbeck had forces enough to hold his own, but he never even attempted the conquest of British East Africa or the Belgian Congo, and the most nervous anticipation could not picture him as a serious danger to other dominions. He was therefore left very much to himself until the South African Union, having set its own house in order and secured its frontiers by expelling German rule from the southern part of the continent, was able to lend its military power and its generalship to the task of reducing the Germans in East Africa. It was formidable enough, not so much from the opposition of man as because of the obstacles nature placed in the way. A tropical climate, torrential rains which played havoc with transport, the tzetze-fly which slew beasts of burden in hundreds of thousands, impenetrable forests, impassable swamps, immense mountain masses, and an area almost as large as Central Europe, provided a problem as vast as that of the great Boer War, and more difficult of solution but for the fact that Von Lettow-Vorbeck's forces could not be compared with those of our past antagonists and present allies. Still they were far more dangerous than any we had encountered in our normal wars against native races; for they had been trained by German officers, experts with machine guns and the other scientific equipment of civilized conflict; and three ships at least had eluded the blockade and relieved Von Lettow-Vorbeck's most pressing need of munitions; and he had selected his coloured troops from the hardiest and most bellicose of the native tribes. With their help he had kept the German colony intact until 1916, and even held at Taveta an angle of British East Africa.

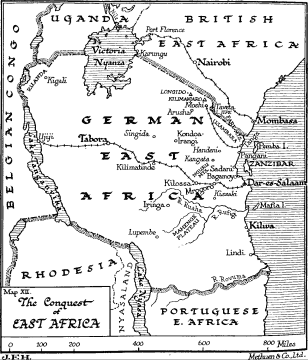

Smith-Dorrien had been selected for the command in the autumn of 1915, but ill-health prevented him from taking it up, and in February 1916 General Smuts arrived at Mombasa to conduct the campaign. Experience had made us shy of enforced landings from the sea; and rejecting the idea of seizing as bases Tanga or Dar-es-Salaam, which would have given him shorter lines of communication with the Cape, Smuts adopted the more circuitous route by the railway from Mombasa, with the design of forcing the gap below Kilimanjaro and driving the Germans southwards, while British and Belgian subsidiary forces impinged upon the enemy's flank from the Lakes, the Congo State, and Nyasa in the west. His advance began on 5 March and Taveta was occupied on the 10th. A frontal attack on the pass between Kilimanjaro and the Pare mountains savoured rather of British than Boer methods, and Smuts preferred to send Van Deventer round the north of Kilimanjaro to turn the German position from Longido and cut off their escape. Van Deventer was successful, and at Moschi blocked the Germans' retreat westwards; they managed, however, to slip away south-eastwards by Lake Jipe, but the Kilimanjaro massif had been cleared, and Smuts established his headquarters at Moschi. His force was now arranged in three divisions, the first under Hoskins, the second under Van Deventer, and the third under Brits; the first consisted of British and Indian troops, the two others of South African. The plan was to strike with the second division from Moschi towards Kondoa Irangi and thence at the German central railway, while the first and third cleared the Pare and Usambara mountains and the coast, and then marched on Handeni and threatened the central railway on a parallel line to Van Deventer's attack. Van Deventer's second division marched with almost incredible speed. He started from Aruscha on 1 April, and by the 19th had driven the Germans from Kondoa Irangi, more than a hundred miles away. In May and June the other divisions cleared the Pave and Usambara mountains, reached Handeni and Kangata, and with naval assistance occupied Tanga, Pangani, Sadani Bay, and Bagamoyo in July and August almost without opposition. Von Lettow-Vorbeck had transferred the bulk of his troops south and then westwards up the central railway to bar Van Deventer's progress; and in the process he had been forced to abandon the north-eastern quarter of the colony. No small part of the north-western province of Ruanda had been lost as well: the Belgians had occupied Kigali and the British had driven the Germans from their shore of Lake Victoria Nyanza. The rapidity and divergence of these attacks, which were admirably timed, distracted Von Lettow-Vorbeck's strategy, and in spite of his interior lines he was unable to offer successful resistance. No sooner did he send troops to bar Smuts' advance from Kangata into the Nguru hills than Van Deventer struck west, south, and south-east from Kondoa Irangi. To the west he took Singida, thus getting behind the Germans on Lake Tanganyika; to the south and south-east he got astride the central railway by 14 July and pushed down it eastwards to Kilossa, which he reached on 22 August. He was now almost due south the Nguru hills, whence Smuts, attacking from the north, had driven the Germans before the middle of August. This converging advance made Mrogoro the only line of retreat, and Smuts planned a complicated outflanking movement to intercept it. They escaped by a track unknown to our forces on the 26th, and prepared to stand south of the central railway in the Ulunguru hills. Smuts was too quick for them, but they repelled a badly-timed attack at Kissaki on 6 September. Their retreat had, however, made the coast untenable: on 3 September the capital Dar-es-Salaam surrendered, and all the remaining ports before the end of the month. Van Deventer, too, had pressed south to the Ruaha on the 10th, the Belgians occupied Tabora on the 19th, and General Northey, advancing from Nyasa in the south-west, had reached Iringa before the end of August, while some Portuguese troops crossed the Rovuma river, the frontier between German East Africa and Mozambique, and made a pretence of marching north. By the end of September the great German colony had been conquered save for the unhealthy south-eastern corner, where only the Mahenge plateau provided a decent habitation for white troops. The campaign had, however, tried the health and endurance of our forces, and three months' respite was now taken for recuperation and reinforcement before the final task of eradicating the Germans from the remnants of their territory. The great difficulty was that, apart from the Mahenge plateau, they were not rooted to any spot, and their elusiveness was illustrated by the fact that the Tabora garrison evaded the encircling forces and joined Von Lettow-Vorbeck at Mahenge. The campaign reopened on 1 January 1917, and consisted of a converging attack on Mahenge by Hoskins from Kilwa on the coast, by Northey from Lupembe, by Van Deventer from Iringa, and by Beves and subsidiary forces from north of the Rufigi. Smuts was summoned on the 29th to England to take part in the imperial conference, and Hoskins succeeded to the chief command. Unprecedented rains impeded our operations; progress became slow, and remained so after Van Deventer replaced Hoskins at the end of May. Not till October was Mahenge occupied by the Belgians. On 26 November half of the German forces under Von Lettow-Vorbeck's lieutenant Tafel were forced to surrender between Mahenge and the Rovuma; but Von Lettow himself escaped across the frontier with sufficient troops to terrorize the Portuguese and maintain himself in their territory until the end of the war. The victor in the East African campaign came in 1917 to a Europe where victory seemed also on the way, for the early spring saw the only German retreat of moment until the war was near its end. The battles of the previous September had convinced the Germans that their line upon the Somme was barely tenable, and they had employed the winter pause to perfect the shorter and better line upon which they had begun to work at Michaelmas. Possibly it was to frustrate these preparations that Haig reopened his campaign so early as he did. On 11 January, the day on which the Allies answered President Wilson's note, British troops began to nibble at the point of the salient on the Ancre which had been created by the battle of the Somme. It was a modest sort of offensive; for it was no part of the Allies' combined plan of operations, which had been settled in conference during November, to launch a first-class attack across the devastated battlefield of the Somme. That wasted area was as effective a barrier as a chain of Alps to military pressure, and the Germans were thus left free to withdraw from their salient without much risk of disaster. They did not contemplate any serious stand, and until the Allies were ready to strike at the flanks of their position the Germans could afford to retreat at a pace which was not seriously hustled by our advance. They showed as much promptitude, foresight, and skill in retirement as they had done in their advance; they suffered few casualties and had no appreciable loss in guns or prisoners. The details of the movement were therefore of little moment, and owed the attention they attracted to the habit of measuring progress in war by miles marked on a map. It was the end of January before the preliminary operation of clearing the Beaumont-Hamel spur was completed, and the apparently substantial advance began with the fall of Grandcourt on 7 February. A more ambitious attack on Miraumont from the south of the Ancre was somewhat disconcerted on the 17th by a German bombardment of our troops as they assembled, although the night was dark and misty; for even in France the Germans found spies to work for them, and a number of executions for treachery failed to prevent knowledge of our plans from occasionally reaching the enemy. A week later the German retreat extended, and Warlencourt, Pys, Miraumont, and Serre were evacuated. Again the Germans stopped for a time to breathe, and it was not till 10 March that Irles, a bare mile from Miraumont, was abandoned. By that time the Germans had only rearguards and patrols left either north or south of the Somme, and when on the 17th a general Allied advance was ordered it encountered little resistance. The area of the German withdrawal had spread over a front of a hundred miles from Arras in the north to Soissons in the south. On that day British troops occupied Bapaume, while the French, whose line we had taken over as far as the river Avre, proceeded to liberate scores of villages between it and the Aisne. On that day, too, by one of the apparent illogicalities of French politics, M. Briand's Cabinet, which had held office for the unusual period of eighteen months, resigned. The German tide rolled sullenly and slowly back for another fortnight. Péronne, Nesle, and Chaulnes fell on the 18th, Chauny and Ham on the 19th, and on the 20th French cavalry were within five miles of St. Quentin. By the end of March the British line ran from a mile in front of Arras to the Havrincourt wood, some seven miles from Cambrai, and thence southwards to Savy, less than two miles from St. Quentin. Thence the French line ran to Moy on the Sambre canal, behind La Fère, which the Germans had flooded, and through the lower forest of St. Gobain to the plateau north-east of Soissons. The German resistance had gradually stiffened, and there was a good deal of local fighting in the first week of April while the Allies were testing the strength of the positions behind which the Germans had taken shelter. We called them the Hindenburg lines, and believed that the Germans had so named them to give them a nominal invincibility which they did not possess in fact. In Germany they were known as the Siegfried lines, a name which properly only applied to the sector between Cambrai and La Fère which was also protected by the St. Quentin canal. That was the front of the new German position; its flanks rested on the Vimy Ridge to the north, and on the St. Gobain forest and the Chemin des Dames to the south. It was a better and shorter line than that which the battles of 1914 had left to the combatants without much choice on either side, and the Germans were right enough in claiming that the Hindenburg lines were selected by themselves. Their retreat thereto was not, however, a matter of choice except in so far as they preferred it to the disaster which would otherwise have overtaken them in their more exposed positions. As a retreat the movement could hardly have been more successfully carried out; but the military distinction was marred by moral disgrace. For destruction was pushed to the venomous length of maiming for years the orchards of the peasantry in the abandoned territory. The crime may have been no more than a characteristic expression of militarist malevolence and stupidity; but it may also have been calculated to bar the path to peace by agreement and to force on the German people the choice, as a Junker expressed it later, between victory and hell. The success of the German withdrawal discounted our spring offensive, not because any attack was designed on the Somme, but because the Hindenburg lines and the desert before them gave that part of the German front a security which enabled the German higher command to divert reserves from its defence to that of the threatened wings. Here preparations had been begun by both the French and the British before the German retreat, and it had barely reached its limit when on Easter Monday, 9 April, Haig attacked along the Vimy Ridge and in front of Arras. Since 21 March a steady bombardment had been destroying the German wire defences and harassing their back areas, and in the first days of April it rose to the pitch which portended an attack in force. Since the battle of Loos in September 1915 our front had sagged a little, and points like the Double Crassier had been recovered by the Germans. So, too, the French capture of the Vimy heights, which had been announced in May that year, proved something of a fairy tale, and in April 1917 our line ran barely east of Souchez, Neuville, and the Labyrinth. It was held by Allenby's Third Army, which joined Gough's Fifth just south of Arras, and by Horne's First, which extended Allenby's left from Lens northwards to La Bassee. The Germans had three lines of defences for their advanced positions, and then behind them the famous switch line which hinged upon the Siegfried line at Quéant and ran northwards to Drocourt, whence quarries and slag-heaps linked it on to Lens (see Maps, pp. 79, 302). This line had not been finished at the beginning of April, and hopes were no doubt entertained that complete success in the battle of Arras, reinforced by Nivelle's contemplated offensive on the Chemin des Dames, would break these incomplete defences and thus turn the whole of the Hindenburg lines. At dawn on Easter Monday the British guns broke out with a bombardment which marked another stage in the growing intensity of artillery fire, and obliterated the first and then the second German line of trenches along a front of some twelve miles. To the north the Canadians under Sir Julian Byng carried the crest of the Vimy Ridge, and by nine o'clock had mastered it all except at a couple of points. Farther south troops that were mainly Scottish captured Le Folie farm, Blangy, and Tilloy-lez-Mofflaines, while a fortress known as the Harp, and more formidable than any on the Somme, was seized by a number of Tanks. The greatest advance of the day was made due east of Arras, where the second and third German lines were taken and Feuchy, Athies, and Fampoux were captured. On the morrow the Canadians completed their hold on the Vimy Ridge, and Farbus was taken just below it. On the 11th the important position of Monchy, which outflanked the end of the Siegfried line, was carried after a fierce struggle; and on the 12th and the following days the salient we had created was widened north and south of Monchy. The capture of Wancourt and Heninel broke off another fragment of the Siegfried line, while to the north our advance spread up to the gates of Lens; the villages of Bailleul, Willerval, Vimy, Givenchy-en-Gohelle, Angres, and Lievin, with the Double Crassier and several of the suburbs of Lens, fell into our hands. The Germans appeared to have nothing left but the unfinished Drocourt-Quéant switch line between them and a real disaster. The battle of Arras was the most successful the British had fought on the Western front since the Germans had stabilized their defences. Our bombardment was heavier than the enemy's, and was far more effective against his wire entanglements and trenches than it had ever been before; and the new method of locating hostile batteries by tests of sound enabled our gunners to put many of them out of action. Nor throughout the war was there a finer achievement than the Canadian capture of the Vimy Ridge or the British five-mile advance in a few hours to Fampoux. The German losses in men and guns also exceeded any that the British had yet inflicted in a similar period; in the first three days of the battle some 12,000 prisoners and 150 guns were taken. The battle did not succeed in converting the war from one of positions into one of movement; but if the Vimy position could be so completely demolished in two or three days, there seemed little prospect of permanence for any German stronghold in France, and a few repetitions of the battle of Arras bade fair to make an end of the Hindenburg lines and of the German occupation of French territory. April along the Western front in 1917 wore a fair promise of spring. Nor was it without its hopes in other spheres. Maude's conquest of Baghdad produced other fruits in the East, including a welcome change in the situation in Persia. The fall of Kut in the April before had enabled the Turks to turn against the Russians and drive Baratov's adventurous force back from Khanikin into the mountains and even east of Hamadan; but Maude's advance cut the Turks off from their base at Baghdad and threatened their line of retreat to Mosul. The Turks were in a trap: Baratov resumed his advance from the north-east, while Maude pushed up from the south-west: Khanikin was the trap-door, and Halil, the Turkish commander, made skilful efforts to keep it open. A strong screen of rearguards held up the Russians at the Piatak pass, while other troops reinforced from Mosul barred Maude's advance at Deli Abbas and on the Jebel Hamrin range. By the end of March the bulk of Halil's forces were through, and Maude had to content himself with linking up with the Russians at Kizil Robat and driving the Turks from the Diala after their troops in Persia had escaped. Their junction with those from Mosul enabled Halil to resume the offensive, but his counter-attack was repulsed on 11-12 April, and Maude proceeded to extend his defences far to the north and west of Baghdad. Feluja on the Euphrates had already been occupied in March, and the Turks driven up the river to Ramadie; and on 23 April Maude completed his advance up the Tigris by the capture of Samara, where the section of the railway running north from Baghdad came to an end. Hundreds of miles separated it from the other railhead at Nisibin, and with his front pushed out on the rivers to eighty miles from Baghdad, and with the Russians in touch with his right and holding the route into Persia, Maude might well rest for the summer content with the security of his conquests. He had done single-handed what had been planned for a joint Anglo-Russian campaign, with Russia taking the lion's share (see Map, p. 177*). In the spring of that year it looked, indeed, as though the British Empire alone was making any headway against the enemy Powers. Even on the cosmopolitan Salonika front offensive action was left to British troops, and at no time during the war did any but troops of the British Empire partake in the defence of its dominions and protectorates. These were all safe enough by the middle of April 1917, and those that were within reach of the enemy were being used as bases for attack upon his forces. Maude, with his army based upon India had now blocked the southern route into Persia, and Sir Archibald Murray was advancing into Palestine. The capture of Rafa on the frontier was followed on 28 February by that of Khan Yunus, five miles within the Turkish border, and the Turks under their German general Kressenstein withdrew to Gaza. There, on 26 March, they were attacked by Sir Charles Dobell, of Cameroon fame, with three infantry and two mounted divisions, including a number of Anzacs. The design was to surround and capture the Turkish forces in Gaza, and the only chance of success lay in the suddenness of the blow and its surprise. For Dobell's base was distant, his men had to drink water brought from Egypt, and in spite of the railway he had not at the front stores, equipment, or troops for a lengthy struggle, while the Turks could bring up superior reinforcements. A sea fog robbed him of two hours' precious time; and although the Wady Ghuzze and other defences of Gaza were taken and a force of Anzacs actually got behind Gaza and were fighting in its northern outskirts at sunset, night fell with the task unfinished and the British divisions out of touch on their various fronts. A retirement was accordingly ordered, and on the morrow Kressenstein counter-attacked. He was driven back with considerable losses, and although Dobell had failed to take Gaza he had reached the Wady Ghuzze and secured the means of bringing his railhead right up to the front of battle. With a few weeks' respite for reinforcement and reorganization, April might yet see the British well on the way to Jerusalem; for Arras was not intended to stand alone, and in every sphere of war the Allies had planned a simultaneous offensive (*see Map, p. 352*). But if hope was bright in the East, it was pallid compared with the certainty of ultimate triumph which blazed from the West across the Atlantic; for on the 5th of that April of promise the great Republic, with a man-power, wealth, and potential force far exceeding those of any other of Germany's foes, entered the war against her and made her defeat unavoidable save by the suicide of her European antagonists. It was not a sudden decision, for a people with such varied spiritual homes as the American, spread over so vast a territory, and looking some eastward across the Atlantic and others westward across the Pacific, but all far removed from European politics and cherishing an inherited aloofness from the Old World and a rooted antipathy to imperialisms of every sort, could not easily see with one eye or achieve unanimity in favour of a vast adventure to break with their past and unite their fortunes with those of the Old World they had left behind. We were accustomed to fighting in Europe against overweening power; the United States had taken their stand on a splendid isolation. Their first president had warned them against entangling alliances, and their fifth had erected into the Monroe Doctrine the principle of abstention from European quarrels. For a century that principle had been the pole-star of American foreign policy; no other people had such a wrench to make from their moorings before they could enter the war, and no other people can understand what it cost the Americans to cut themselves adrift from their haven of democratic pacifism in order to fight for the freedom of another world. But Fate was too strong for schismatic tradition, and the two worlds had merged into one. The shrinking of space and expansion of mind was abolishing East and West, and the two hemispheres had become one exchange and mart of commodities and ideas. They could not continue to revolve on diverse political axes, and neither was safe without the other's concurrence. To the German cry of weltmacht must sooner or later respond the American cry of weltrecht; for the war was a civil war of mankind, and upon its issue would hang the future of human government. Intervention was inevitable, not so much because the Kaiser had said he would stand no nonsense from America as because, if America was to stand no nonsense from him after victory, she would have to turn the New World into an armed camp like the Old and run the same race to ruin. The old peace and isolation were in any case gone, and the choice was between war for the time, with the prospect of permanent peace on the one hand, and peace for the time, with the permanent prospect of war on the other. There was no other way, and Germany forced the American people to realize their dilemma. President Wilson had seen it earlier than the majority of his fellow-countrymen; but for a statesman a vision of the truth is an insufficient ground for acting upon it. He is bound, indeed, not to act upon it until he can carry with him the State he governs; otherwise he ceases to be a statesman and sinks or rises into the missionary. The zealot is ever ready to break his weapon upon the obstacle he wishes to remove, but the statesman who destroys national unity in his zeal for war does not help to win it; and American intervention was both useless and impossible until the President could act with his people behind him. Nor, as official head of the State, could he play the irresponsible part of an advocate; if he believed war to be inevitable in his country's interests, it was for him to convince the people not by argument, but by his conduct of American affairs. Idealism entered more largely into his policy than that of most statesmen, but it was bound to American mentality and national interests; for ideals which do not affect national interests do not appeal to the majority in any nation, and the lawlessness which trampled on Belgian neutrality made less impression across the Atlantic than that which destroyed American lives and property. A subsidiary cause of delay in American intervention was the absorption of the United States in the presidential contest of 1916, but President Wilson's re-election in November gave him a freer hand than was possessed by any other democratic statesman. No American president is ever elected for a third term of office, and Mr. Wilson had no need to keep his eye on his prospects for 1920. He must, indeed, secure the assent of Congress before war could be declared, but in both Houses his party had secured a majority in November. The decisive step was not, however, taken by President Wilson, but by the German Government, and America was as much forced into war in 1917 as we were in 1914; and in both cases it was their view of military necessity which drove the Germans into political suicide. They could not, they thought in 1914, cope with Russia until they had first beaten France, and they could not beat France in time unless they trampled a way through Belgium. So in the early days of 1917, not foreseeing the fortune which the Russian revolution was to bring them, they saw no prospect of victory save through the ruin of England by means of their submarines. The Eastern and Western fronts were too strong for a successful offensive against either, the military situation was growing desperate, and their offers of peace had been scorned; the war went on in their despite, and their real offensive for 1917 was the submarine campaign. It was adopted because there was no opening on land and no hope of success in a naval battle; and its adoption justified those who held that the remedy was worse than the disease and that unrestricted submarine warfare would bring the United States into the war before it drove Great Britain out. As late as 22 January, President Wilson, while depicting the sort of peace which would commend itself to the American people, disavowed any intention of helping to secure it by force of arms. But on the 31st Germany revoked her promise given on 4 May 1916 that vessels other than warships would not be sunk without warning, and announced her resolve forthwith to wage submarine war without any restriction. Later on Herr Bethmann-Hollweg stated that the promise had only been given because Germany's preparations were incomplete, and was revoked as soon as they were ready. The President's answer was prompt: on 3 February the German ambassador was given his passports and Mr. Gerard was recalled from Berlin. But the invitation to other neutrals to follow the President's lead was declined on this side of the Atlantic. Switzerland, without any seaboard, was not concerned with submarine warfare, and other neutrals were too much under the influence of German blandishments or terror to risk war in defence of their rights; they preferred to abandon their sailings to British ports. At first the President contemplated no more than an armed neutrality, and proposed to equip all American mercantile vessels for self-defence. But the sinking of American ships and loss of American lives began to rouse popular anger; sailings stopped at the ports, the railways became congested with goods seeking outlet, and the remotest inland districts felt the effects of the German campaign. In March, too, the Russian revolution removed a stumbling-block to co-operation with the Entente, for American public opinion had always been sensitive to the iniquity of the old regime in Russia. At length the President summoned a special session of Congress, and on 2 April recommended a declaration of war. It was adopted in the Senate on the 4th by 82 votes to 6, and by the House of Representatives on the 5th by 373 to 50. Of the ultimate issue of the war there could now be no doubt. Time would be needed for the United States to mobilize its resources and train its armies, and the extent to which they might be required would depend upon the course of events in Europe. But the Americans were not a people to turn back having put their hand to the plough, and with their forces fully deployed they would alone be more than a match for the German Empire. Victory might be delayed, but its advent was assured, and the first fortnight of April saw the hopes of the Allies rise higher than since the war began. << Previous | Contents | Next >> |

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||