|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

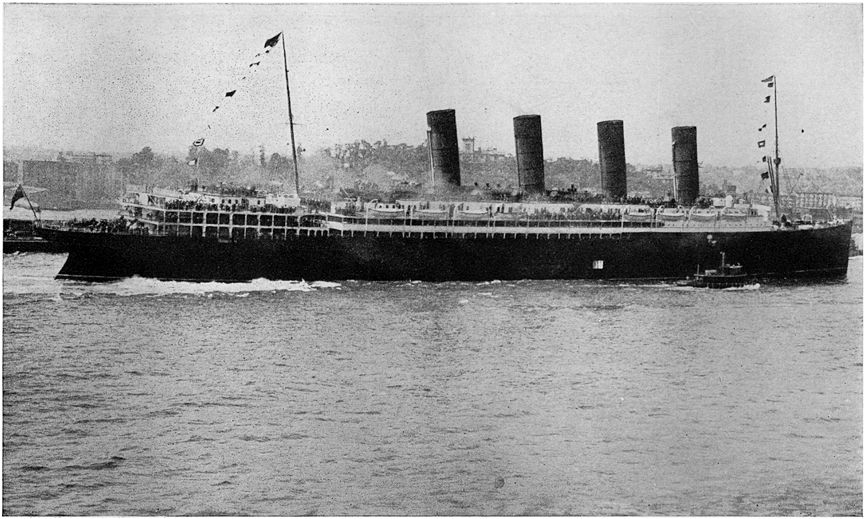

<< Previous | Contents | Next >> CHAPTER IV The Sinking of the LusitaniaSINKING OF THE "LUSITANIA" The assasination of the Austrian Crown Prince started the war, but the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania by a German submarine escalated the war by contributing (together with the furor over the Zimmerman Telegram) to United States involvement in the war. The arrival of American troops later in the war would tip the balance decisively in favour of the Allies. The sinking of the unarmed vessel was generally regarded as an outrageous act of murder by the American public and British propaganda exploited the sinking to the fullest. However, the sinking of the Lusitania was perhaps more morally ambiguous. Firstly, the Germans had published notices in the American newspapers (America was the then neutral) warning that any vessel entering a military zone around the British Isles would be subject to sinking. Secondly, it was the practice of the British to fly the flags of neutral countries in order to avoid attack, so the German submarine could not have known for certain that the ship was American. Thirdly, the Lusitania was in fact carrying ome munitions and other supplies for the British war effort. On the 7th of May, 1915, came the most sensational act committed by German submarines since the war had started—the sinking of the Cunard liner Lusitania. The vessel which did this was one of the U-39 class. In her last hours above water the giant liner was nearing Queenstown on a sunny day in a calm sea. When about five miles off shore, near Old Head of Kinsale, on the southeastern coast of Ireland, a few minutes after two o'clock, while many of the passengers were at lunch and a few of them on deck, there came a violent shock.

Five or six persons who had been on deck had noticed, a few moments before, the wake of something that was moving rapidly toward the ship. The moving object was a torpedo, which struck the hull to the forward on the starboard side and passed clean through the ship's engine room. She began to settle by the bows immediately, and the passengers, though cool, made rushes for lifebelts and for the small boats. The list of the boat made the launching of some of these impossible. The scenes on the decks of the sinking liner were heartrending. Members of families had become separated and ran wildly about seeking their relatives. The women and children were put into the lifeboats—being given preference. "I was on the deck about two o'clock," narrated one of the survivors, "the weather was fine and bright and the sea calm. Suddenly I heard a terrific explosion, followed by another, and the cry went up that the ship had been torpedoed. She began to list at once, and her angle was so great that many of the boats on the port side could not be launched. A lot of people made a rush for the boats, but I went down to my cabin, took off my coat and vest and donned a lifebelt. On getting up again I found the decks awash and the boat going down fast by the head. I slipped down a rope into the sea and was picked up by one of the lifeboats. Some of the boats, owing to the position of the vessel, got swamped, and I saw one turn over no less than three times, but eventually it was righted." Not all of the women and children got off the liner into the small boats. "Women and children, under the protection of men, had clustered in lines on the port side of the ship," reported another survivor. "As the ship made her plunge down by the head, she finally took an angle of ninety degrees, and I saw this little army slide down toward the starboard side, dashing themselves against each other as they went, until they were engulfed." Even under the stress of avoiding death the sight of the sinking hull was one that held the attention of those in the water. One of the sailors said afterward: "Her great hull rose into the air and neared the perpendicular. As the form of the vessel rose she seemed to shorten, and just as a duck dives so she disappeared. She went almost noiselessly. Fortunately her propellers had stopped, for had these been going, the vortex of her four screws would have dragged down many of those whose lives were saved. She seemed to divide the water as smoothly as a knife would do it." Twenty minutes after the torpedo had struck the ship she had disappeared beneath the surface of the sea. "Above the spot where she had gone down," said one of the men who escaped death, "there was nothing but a nondescript mass of floating wreckage. Everywhere one looked there was a sea of waving hands and arms, belonging to the struggling men and frantic women and children in agonizing efforts to keep afloat. That was the most horrible memory and sight of all." Fishing boats and coasting steamers picked up many of the survivors some hours after the disaster. The frightened people in the small boats pulled for the shore after picking up as many persons as they dared without swamping their boats. Some floated about in the waters for three and four hours, kept up by their lifebelts. Some, who were good swimmers, managed to keep above water till help came; others became exhausted and sank. Probably the best story, covering the entire period from the time the ship was hit till the survivors were landed at Queenstown, was told by Dr. Daniel V. Moore, an American physician: "After the explosion," said Dr. Moore, "quiet and order were soon accomplished by assurances from the stewards. I proceeded to the deck promenade for observation, and saw only that the ship was fast leaning to the starboard. I hurried toward my cabin below for a lifebelt, and turned back because of the difficulty in keeping upright. I struggled to D deck and forward to the first-class cabin, where I saw a Catholic priest. "I could find no belts, and returned again toward E deck and saw a stewardess struggling to dislodge a belt. I helped her with hers and secured one for myself. I then rushed to D deck and noticed one woman perched on the gunwale, watching a lowering lifeboat ten feet away. I pushed her down and into the boat, then I jumped in. The stern of the lifeboat continued to lower, but the bow stuck fast. A stoker cut the bow ropes with a hatchet, and we dropped in a vertical position. "A girl whom we had heard sing at a concert was struggling, and I caught her by the ankle and pulled her in. A man I grasped by the shoulders and I landed him safe. He was the barber of the first-class cabin, and a more manly man I never met. "We pushed away hard to avoid the suck, but our boat was fast filling, and we bailed fast with one bucket and the women's hats. The man with the bucket became exhausted, and I relieved him. In a few minutes she was filled level full. Then a keg floated up, and I pitched it about ten feet away and followed it. After reaching the keg I turned to see what had been the fate of our boat. She had capsized. Now a young steward, Freeman, approached me, clinging to a deck chair. I urged him to grab the other side of the keg several times. He grew faint, but harsh speaking roused him. Once he said: 'I am going to go.' But I ridiculed this, and it gave him strength. "The good boat Brock and her splendid officers and men took us aboard. "At the scene of the catastrophe the surface of the water seemed dotted with bodies. Only a few of the lifeboats seemed to be doing any good. The cries of 'My God!' 'Save us!' and 'Help!' gradually grew weaker from all sides, and finally a low weeping, wailing, inarticulate sound, mingled with coughing and gargling, made me heartsick. I saw many men die. Some appeared to be sleepy and worn out just before they went down." Officials of the Cunard Line claimed afterward that three submarines had been engaged in the attack on the liner, but, after all evidence had been sifted, the claim made by the Germans that only one had been present was found to be true. The commander Page 1426 of the submarine had evidently been well informed as to just what route the liner would take. Trouble with her engines, which developed after she had left New York, had brought her speed down to 18 knots, a circumstance which was in favor of the attacking vessel, for it could not have done much damage with a torpedo had she been going at her highest speed; it would have given her a chance to cross the path of the torpedo as it approached. No sign of the submarine was noticed by the lookout or by any of the passengers on the Lusitania until it was too late to maneuver her to a position of safety. A few moments before the white wake of the approaching torpedo was espied, the periscope had been seen as it came to the surface of the water. From that moment onward the liner was doomed. The German admiralty report of the actual sinking of the ship, which was issued on the 14th of May, 1915, was brief. It read: "A submarine sighted the steamship Lusitania, which showed no flag, May 7, 2.20 Central European time, afternoon, on the southeast coast of Ireland, in fine, clear weather. "At 3.10 o'clock one torpedo was fired at the Lusitania, which hit her starboard side below the captain's bridge. The detonation of the torpedo was followed immediately by a further explosion of extremely strong effect. The ship quickly listed to starboard and began to sink. "The second explosion must be traced back to the ignition of quantities of ammunition inside the ship." One of the effects of the sinking of the Lusitania was to cut down the number of passengers sailing to and from America to Europe on ships flying flags of belligerent nations. Attacks by submarines on neutral ships did not abate, however, for on the 15th of May, 1915, the Danish steamer Martha was torpedoed in broad daylight and in view of crowds ashore off the coast of Aberdeen Bay. The sinking of ships in the "war zone" continued in spite of rumors that the German admiralty was expected to discontinue operations of the submarines against merchantmen on account of the unfriendly feeling aroused in neutral nations, particularly the United States. On the 19th of May, 1915, came the news that Page 1427 the British steamship Dumcree had been torpedoed off a point in the English Channel. A torpedo fired into her hull failed to sink her immediately, and a Norwegian ship came to her aid, passing her a cable and attempting to tow her to port. But the submarine returned, and fearing attack, the Norwegian ship made off. A second torpedo fired at the Dumcree had better effect than the first one, and she began to settle. When the submarine left the scene the Norwegian steamship again returned to the Dumcree and managed to take off all of her crew and passengers. Three trawlers, one of them French, were sunk in the same neighborhood during the next forty-eight hours. As soon as Italy entered the war an attempt was made by the Teutonic Powers to establish the same sort of submarine blockade in the Adriatic which obtained in the waters around Great Britain. This was evinced when the captain of the Italian steamship Marsala reported on May 21, 1915, that his ship had been stopped by an Austrian submarine, but the latter not wishing to disclose its location to the Italian navy, allowed his ship to proceed unharmed. The suspicion that the German admiralty maintained bases for their submarines right on the coasts of Great Britain where the submersible craft could obtain oil for driving their engines, as well as supplies of compressed air and of food for the crew, was confirmed on the 14th of May, 1915, when it was reported that agents of the British admiralty had discovered caches of the kind at various points in the Orkney Islands, in the Bay of Biscay, and on the north and west coasts of Ireland. In order to damage shipping in the "war zone" by having ships go wrong through having no guiding lights an attack was made by a German submarine on the lighthouse at Fastnet, on the southern coast of Ireland, on the night of May 25, 1915. Shortly after nine in the evening the submarine was sighted in the waters near the lighthouse by persons on shore. She was about ten miles from Fastnet, near Barley Cove. When she came near enough to the lighthouse to use her deck guns, men on shore opened fire on her with rifles, and she submerged, not to reappear in that neighborhood again. But this same submarine managed to do other damage. The American steamship Nebraskan was in the neighborhood on its way to New York. The sea was calm and the ship was traveling at 12 knots, when some time near nine o'clock in the evening a shock was felt aboard. A second later there came a terrific explosion, and a subsequent investigation showed that a large hole, 20 feet square, had been torn in her starboard bow, not far from the water line. When she began to settle the captain ordered all hands into the small boats. They stayed near the damaged ship for an hour and saw that she was not going to sink. When they got aboard again they found that a bulkhead was keeping out the water sufficiently to allow her to proceed under her own steam. In crippled condition she made for port, being convoyed later by two British warships which answered her calls for help. In spite of the sharp diplomatic representations which were at the time passing back and forth between Germany and the United States over the matter of the German submarine warfare, the craft kept up as active a campaign against merchant ships as they did before the issues became pointed. On May 28, 1915, there came the news that three more ships had been sent to the bottom. The Spennymoor, a new ship, was chased and torpedoed off Start Point, near the Orkney Islands. Some of her crew were drowned when the lifeboat in which they were getting away capsized, carrying them down. On the same day the large liner Argyllshire was chased and fired upon by the deck guns of a hostile submarine, but she managed to get away. Not so fortunate, however, was the steamship Cadesby. While off the Scilly Islands on the afternoon of May 28, 1915, a German submarine hailed her, firing a shot from a deck gun across her bows as a signal to halt. Time was given for the crew and passengers to get into small boats, and when these were at a distance from the ship the deck guns of the submarine were again brought into action, and after firing thirty shots into her hull they sank her. The third victim was the Swedish ship Roosvall. She was stopped and boarded off Malmoe by the crew of a German submarine. After examining her papers they permitted her to proceed, but later sent a torpedo into her, sinking her. A new raider, the U-24, made its appearance in the English Channel during the last week in May, 1915. On the twenty-eighth of the month this submarine sank the liner Ethiope. The captain of the steamship attempted some clever maneuvering, which did not accomplish its object. He paid no attention to a shot from the deck guns of the submarine which passed across his bow. The hostile craft then began to circle around the liner, while the rudder of the latter was put at a wide angle in an effort to keep either stern or bow of the ship toward the submarine, thus making a poor target for a torpedo. But the commander of the submarine saw through the movement and ordered fire with his deck guns. After shells had taken away the ship's bridge and had punctured her hull near the stern the crew and passengers were ordered into the small boats. They had hardly gotten twenty feet from their ship when she was rent by a violent explosion and went down. The transatlantic liner Megantic had better luck, for she managed to escape a pursuing submarine on May 29, 1915, as she was nearing Queenstown, Ireland, homeward bound. A notable change in the methods adopted by the commanders of submarines as a result of orders issued by the German admiralty in answer to the protests throughout the press of the neutral nations after the sinking of the Lusitania was the giving of warning to intended victims. By the end of May, 1915, in almost every instance where a German submarine stopped and sank a merchantman the crew was given time to get off their ship and the submarine did not hesitate to show itself. In fact, warning to stop was generally given when the submarine's deck was above water and the gun mounted there had the victim "covered." This was done in the case of the British steamship Tullochmoor, which was torpedoed off Ushant near the most westerly islands of Brittany, France. On the 1st of June, 1915, there came the news of the sinking of the British ship Dixiana, near Ushant, by a German submarine which approached by aid of a clever disguise. The crew managed Page 1430 to get off the ship in time; when they landed on shore they reported that the submarine had been seen and on account of sails which she carried was thought to be an innocent fishing boat. The disguise was penetrated too late for the Dixiana to make its escape. The clear and calm weather which came with June, 1915, made greater activity on the part of German submarines possible. On the 4th of June, 1915, it was reported by the British admiralty that six more ships had been made victims, three of them being those of neutral countries. In the next twenty-four hours the number was increased by eleven, and eight more were added by the 9th of June, 1915. On that date Mr. Balfour, Secretary of the British admiralty, announced that a German submarine had been sunk, though he did not state what had been the scene of the action. At the same time he announced that Great Britain would henceforth treat the captured crew of submarines in the same manner as were treated other war prisoners, and that the policy of separating these men from the others and of giving them harsher treatment would be abandoned. On the 20th of June, 1915, the day's reports of losses due to the operations of German submarines, issued by the British Government, contained the news of the sinking of the two British torpedo boats, the No. 10 and the No. 20. No details were made public concerning just how they went down. On the same day the Italian admiralty announced that a cache maintained to supply submarines belonging to the Teutonic Powers and operating in the Mediterranean, had been discovered on a lonely part of the coast near Kalimno, an island off the southwest coast of Asia Minor. Ninety-six barrels of benzine and fifteen hundred barrels of other fuel were found and destroyed. It was believed that this supply had been shipped as kerosene from Saloniki to Piraeus. How submarines belonging to Germany had reached the southern theatre of naval warfare had been a matter of speculation for the outside world. But on the 6th of June, 1915, Captain Otto Hersing made public the manner in which he took the U-51 on a 3,000 mile trip from Page 1431 Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea to Constantinople. He was the commander who managed to torpedo the British battleships Triumph and Majestic. He received his orders to sail on the 25th of April, 1915, and immediately began to stock his ship with extra amounts of fuel and provisions, allowing only his first officer and chief engineer to know the destination of their craft. He traveled on the surface of the water as soon as he had passed the guard of British warships near the German coast; traveling "light" allowed him to make six or seven knots more in speed. As he passed through the "war zone" he kept watch for merchantmen which might be made victims of his torpedo tubes. His craft was sighted by a British destroyer, however, off the English coast and he had to submerge to escape the fire of the destroyer's guns. He then proceeded cautiously down the coast of France, encountering no hostile ships. When within one hundred miles of Gibraltar he was again discovered by British destroyers, but again managed to escape by submerging his craft. Passage through the Strait of Gibraltar was made in the early morning hours, while a mist hung near the surface of the water and permitted no one at the fort to see the wake of the U-51's periscope. Once inside the Mediterranean he headed for the south of Greece, escaping attack from a French destroyer and proceeding through the Ægean Sea to the Dardanelles. The journey ended on the 25th of May, just one month after leaving Wilhelmshaven. The British ships Triumph and Majestic were sighted early in the morning, but attack upon them was difficult on account of the destroyers which circled about them; one of the destroyers passed right over the U-51 while she was submerged. Captain Hersing brought her to the surface soon afterward and let go the torpedo which sank the Triumph. For the next two days the submarine lay submerged, but came up on the following day and found itself right in the midst of the allied fleet. This time the Majestic was taken as the target for a torpedo and she went down. Again submerging his vessel Captain Hersing kept it down for another day, and when he again came to the surface he saw Page 1432 that the fleets had moved away. He then returned to Constantinople. On the 23d of June, 1915, the British cruiser Roxborough, an older ship, was hit by a torpedo fired by a German submarine in the North Sea, but the damage inflicted was not enough to prevent her from making port under her own steam. The deaths of a number of Americans occurred on the 28th of June, 1915, when the Leyland liner Armenian, carrying horses for the allied armies, was torpedoed by the U-38, twenty miles west by north of Trevose Head in Cornwall. According to the story of the captain of the vessel, the submarine fired two shots to signal him to stop. When he put on all speed in an attempt to get away from the raider her guns opened on his ship with shrapnel, badly riddling it. She had caught fire and was burning in three places before he signaled that he would surrender. Thirteen men had meanwhile been killed by the shrapnel. Some of the lifeboats had also been riddled by the firing from the submarine's deck guns, making it more difficult for the crew to leave the ship. The German commander gave him ample time to get his boats off. To offset the advantage which the Germans had with their submarines the British admiralty commissioned ten such craft during the week of June 28, 1915. These vessels were of American build and design and were assembled in Canada. During the week mentioned they were manned by men sent for the purpose from England. Each was manned by four officers and eighteen men, to take them across the Atlantic. Never before in history had so many submarines undertaken a voyage as great. They got under way from Quebec on July 2, 1915, and proceeded in column two abreast, a big auxiliary cruiser, which acted as their escort steaming in the center. The next large liner which had an encounter with the German submarine U-39 was the Anglo-Californian. She came into Queenstown on the morning of July 5, 1915, with nine dead sailors lying on the deck, nine wounded men in their bunks, and holes in her sides made by shot and shell. She had withstood attack from a German submarine for four hours. Her escape from destruction Page 1433 was accomplished through only the spirit of the captain and his crew, combined with the fact that patrol vessels came to her aid forcing the submarine to submerge. A variety in the methods used by the commanders of German submarines was revealed in the stopping of the Norwegian ship Vega which was stopped on the 15th of July, while voyaging from Bergen to Newcastle. The submarine came alongside the steamship at night and the commander of the submarine supervised the jettisoning of her cargo of 200 tons of salmon, 800 cases of butter, and 4,000 cases of sardines, which was done at his command under threat of sinking his victim. The week of July 15, 1915, was unique in that not one British vessel was made the victim of a German submarine during that period, though two Russian vessels had been sunk. Figures compiled by the British admiralty and issued on the 22d of July, 1915, gave out the following information concerning the attacks on merchantmen by German submarines since the German admiralty's proclamation of a "war zone" around Great Britain went into effect on the 18th of February, 1915. The official figures were as follows:

The first year of the Great War came to an end with the German submarines as active in the "war zone" as they had been during any part of it. On the 28th of July, 1915, the anniversary of the commencement of the war, there was reported the sinking of nine vessels. These were the Swedish steamer Emma, the three Danish schooners Maria, Neptunis, and Lena, the British steamer Mangara, the trawlers Iceni and Salacia, the Westward Ho, and the Swedish bark Sagnadalen. No lives were lost with any of these vessels. The first year of the war closed with a cloud gathered over the heads of the members of the German admiralty raised by the irritation the submarine attacks in the "war zone" had caused. Germany's enemies protested against the illegality of these attacks; neutral nations protested because they held that their rights had been overridden. But the German press showed the feeling of the German public on the matter—at the end of July, 1915, it was as anxious as ever to have the attacks continued. Conflicting claims were issued in Germany and England. In the former country it was claimed that the attacks had seriously damaged commerce; in the latter it was claimed that the damage was of little account. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||