the Archive of World War 1 Photographs and Texts

the Archive of World War 1 Photographs and Texts

Photographs of the Battle of the Mazurian Lakes

The Battle of the Mazurian Lakes (alternate spelling: Battle of the Masurian Lakes) is also known as the Nine Days' Battle. It was a contest between the German and Russian forces, and resulted in a devastating Russian defeat and the annihilation of the Russian X Army.This titanic battle began 7th of February, 1915, and ended on the 16th, when the Russian Tenth Army, consisting of at least eleven infantry and several cavalry divisions, had been driven out of its strongly fortified positions to the east of the Mazurian Lake district, forced across the border, and, having been almost completely surrounded, had been crushingly defeated. Some fighting continued as part of the same action until the 21st of February, 1915, when the pursuit of the defeated Russian army ended.

|

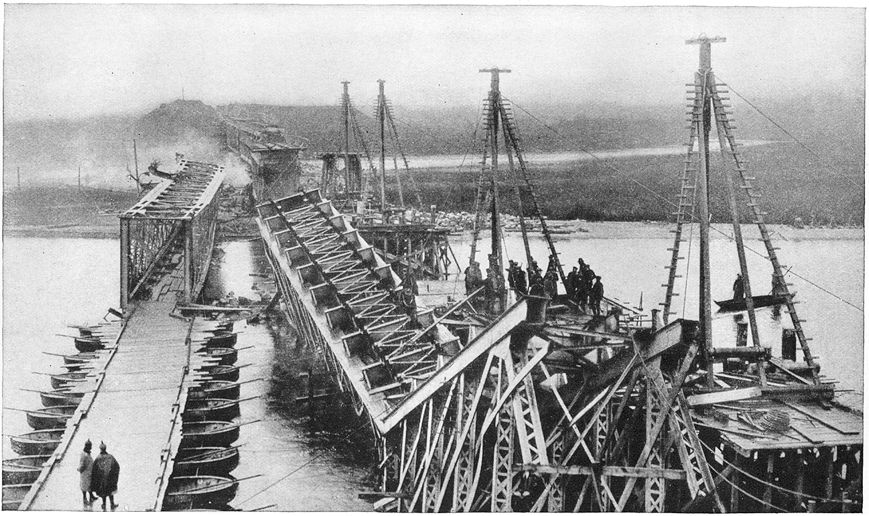

| A bridge on blown up by the Russians in their retreat toward Warsaw. At the left is the pontoon bridge built by the Germans |

The forces engaged in the massive Battle of the Mazurian Lakes were the Russian Tenth Army, consisting, according to the Russian version, of four corps, under General Baron Sievers, and the German East Prussian armies, under General van Eichhorn, operating on the north on the line Insterburg-Lötzen, and General van Bülow on the line Lötzen-Johannisburg to the south of Van Eichhorn. Sources favorable to the Allies represent the strength of General Sievers's army as 120,000 men. They assert that the total German force consisted of nine corps, over 300,000 men. These are said to have included the Twenty-first Corps, which had been with the Crown Prince of Bavaria in the west; three reserve corps, also from the west; the Thirty-eighth and Fortieth Corps, new formations, from the interior of Germany; the equivalent of three corps from other sections of the eastern front; and a reserve corps of the Guard. The German official description of the battle credits the Russians with having had in this sector of the battle front in East Prussia at the beginning of February six to eight army corps, or about 200,000 men.

For months the heavy fighting in the east had centered on other sections of the immense battle line, running from the Baltic to the Carpathians. The second general Russian offensive, the great forward thrust of the Grand Duke Nicholas toward Cracow in the direction of Berlin, aimed through the center of the German defense, had been met, and the German counter thrust toward Warsaw had come to a standstill in the mud of Poland and before the stone-wall defensive of the Russians on the Bsura and the Rawka. Attacks launched by the Russians against the East Prussian frontier, centering at Lyck, in January, 1915, seemed to forebode a fresh Russian offensive intended to sweep back the German armies in this section whose position on the Russian right wing was a continual threat to the communications of the Russian commander in chief.

The Germans, disposing of comparatively weak forces, estimated at three army corps, were compelled to yield a strip of East Prussian territory, and had fallen back to positions of considerable natural strength formed by the chain of Mazurian Lakes and the line of the Angerapp River. They reported their forces standing on the defensive here as 50 per cent Landwehr, 25 per cent Landsturm, and only 25 per cent other troops not of the reserve. Repeated attempts of the Russians to gain possession of these fortified positions had, however, broken down. They had been directed especially against the bridgehead of Darkehmen and the right wing of the German forces in the Paprodtk Hills. Wading up to their shoulders in icy water, the hardy troops of the Third Siberian Corps had attempted in vain to cross the Nietlitz Swamp, between the lakes to the east of Lyck.

At the beginning of February, 1915, finally Von Hindenburg had been able to obtain fresh German forces and to put them in position for an encircling movement against the Russians lying just to the east of the lakes, from near Tilsit to Johannisburg. With the greatest secrecy the reenforcements, hidden from observation by their fortified positions, and the border forces maintaining the defense, were gathered behind the two German wings. The Russians apparently gained an inkling of the big move that was impending about the time the advance against their wings was under way. The first news of the opening of the battle came to the public in a Russian official announcement of the 9th of February, 1915, to the effect that on the 7th the Germans had undertaken the offensive with considerable force in the Goldap-Johannisburg sector. The northern group of Germans began its movement somewhat later from the direction of Tilsit.

Extensive preparations had been made by the German leaders to meet the difficulties of a winter campaign under unfavorable weather conditions. Thousands of sleighs and hundreds of thousands of sleigh runners (on which to drag cannon and wagons), held in readiness, were a part of these preparations for a rapid advance. Deep snow covered the plain, and the lakes were thickly covered with ice. On the 5th of February, 1915, a fresh snowstorm set in, accompanied by an icy wind, which heaped the snow in deep drifts and made tremendously difficult travel on the roads and railways, completely shutting off motor traffic.

The Germans on the south, in order to come into contact with the main Russian forces, had to cross the Johannisburg Forest and the Pisseck River, which flows out of the southernmost of the chain of lakes. The attacking columns made their way through the snow-clad forests with all possible speed, forcing their way through barriers of felled trees and driving the Russians from the river crossings.

Throughout the 8th of February, 1915, the marching columns moved through whirling snow clouds, the Germans driving their men forward relentlessly, so that, in spite of the drifted snow which filled the roads, certain troops covered on this day a distance of forty kilometers. The Germans under General von Page 1516 Falck took Snopken by storm; those under General von Litzmann crossed the Pisseck near Wrobeln. The immediate objectives of these columns were Johannisburg and Biala, where strong Russian forces were posted.

On the 9th the southern column, under Von Litzmann, was attacked on its right flank by Russians coming from Kolna, to the south of them. The German troops repelled the attack, taking 2,500 prisoners, eight cannon, and twelve machine guns. General Saleck took Johannisburg, and Biala was cleared of the Russians. The advance of these southern columns continued rapidly toward Lyck.

The German left wing at the same time fell overwhelmingly on the northern end of the Russian line. On the 9th they took the fortified Russian positions stretching from Spullen to the Schorell Forest and nearly to the Russian border. They had here hard work to force their way through wire entanglements of great strength. Having noticed signs of a retreat on the part of their opponents, these German forces had on the preceding day begun the attack without waiting for the whole of their artillery to come up. The Russians retreated toward the southeast.

Swinging forward toward the Russian border, the German left wing now exerted itself to the utmost to execute the sweeping encircling movement for which the strategy of Von Hindenburg had become famous. The Russian right wing had been turned and was being pressed continually toward the southeast. The German troops rushed forward in forced marches, ignoring the difficulties which nature put in their way. By the 10th of February these columns reached the Pillkallen-Wladislawow line, and by the 11th the main highway from Gumbinnen to Wilkowyszki. The right wing, up to the capture of Stallupohnen, had taken some 4,000 prisoners, four machine guns, and eleven ammunition wagons. The center of this army, at the capture of Eydtkuhnen, Wirballen, and Kibarty, took 10,000 prisoners, six cannon, eight machine guns, numerous baggage wagons, including eighty field kitchens, three military trains and other rolling stock, a large number of gift packages intended for the Russian troops, and, of chief interest to the fighting men, a whole day's provisions.

On the afternoon of February 10 some one and a half Russian divisions had come to a halt in these three neighboring villages: Eydtkuhnen, Kibarty, and Wirballen. Although it was known that the Germans were approaching, it was apparently regarded by the Russians as impossible that pursuers would be able to come up with them in the raging snowstorm. So certain were they of their security that no outposts were put on guard. Only thus could it happen that the Germans, who had not allowed the forces of nature to stop their advance, arrived right at the Russian position on the same day, though with infantry alone and merely a few guns, everything else having been left behind, stuck in the snowdrifts.